Culture in Mergers & Acquisitions

When it comes to Mergers and Acquisitions, one major contributor to the valuation process often gets overlooked: company culture.

If I were to ask you the quickest way across town, you probably wouldn’t tell me a horse and carriage. If I asked to take your picture, you’d expect to pose for a moment or two (not several hours). If you needed to keep your food cool, you wouldn’t bury it underground. This is because we’ve evolved since the mid-19th century, and replaced these outdated methodologies with more effective, present-day alternatives.

In fact, it would probably strike you as bizarre if you saw someone using a typewriter or a child rolling a hoop down the street. Anything from the 1850s would feel entirely out of place in our modern world.

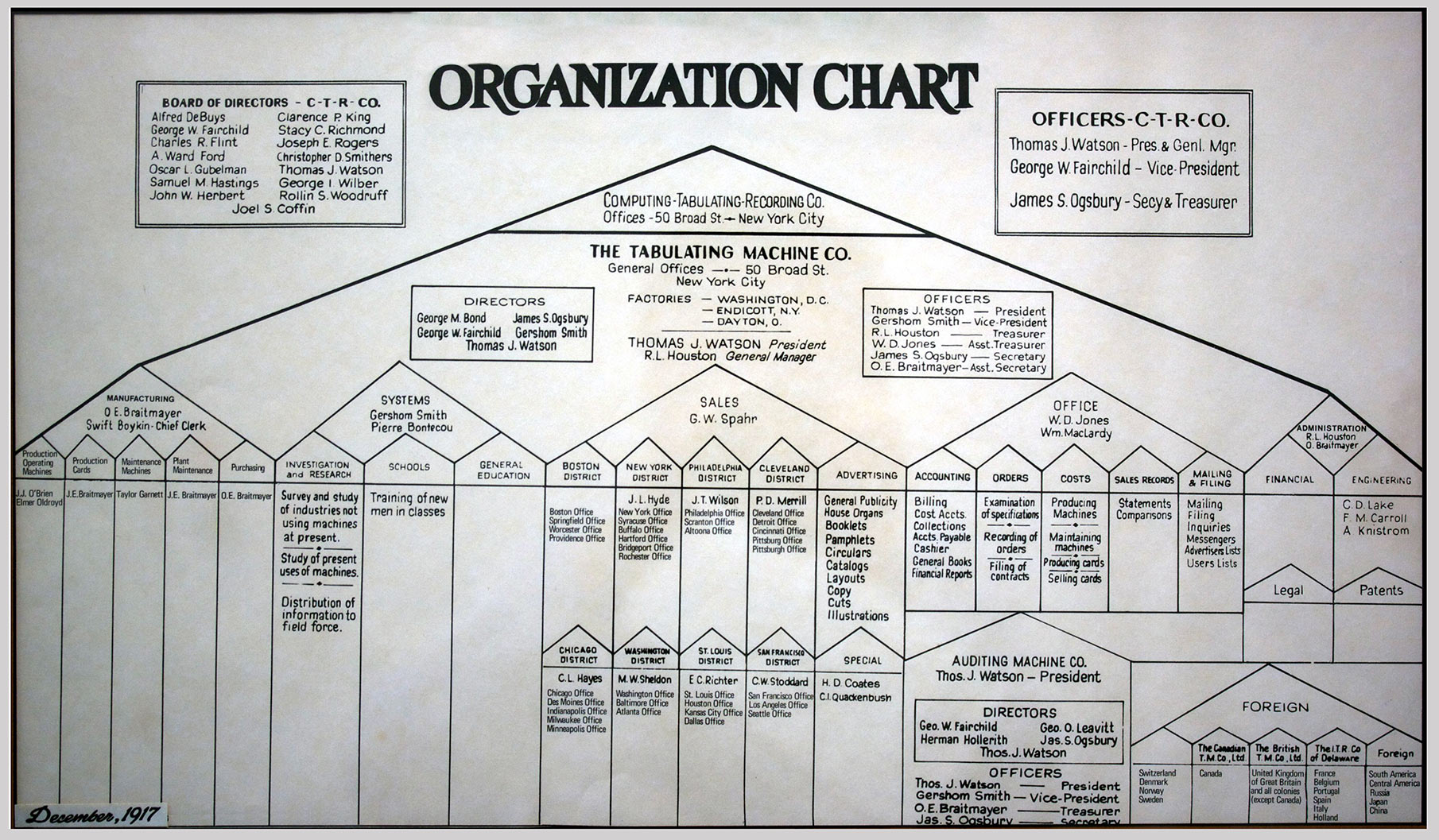

So why are we still using the same org charts?

The first org chart was introduced in 1855 for the Erie Railroad — one of the largest railroad companies of its time, covering more than 500 miles of track and eager to expand. However, this proved unexpectedly difficult. As Daniel McCallum, their newly appointed superintendent, put it:

“A superintendent of a road only fifty miles in length can give the business his personal, professional attention. […] But, in governing five hundred miles of track, a very different challenge exists. I am fully convinced that a larger scale railroad and system demands more rigor and perfection in the operations management discipline.”

Thus, the modern org chart was born.

It was a revolutionary achievement, to be sure. It brought order to a distributed workforce and facilitated the transport of goods throughout the Northeastern United States — charting a course for many other organizations to follow.

But does it strike you as odd that the vast majority of businesses today still use the exact same model developed almost 200 years ago?

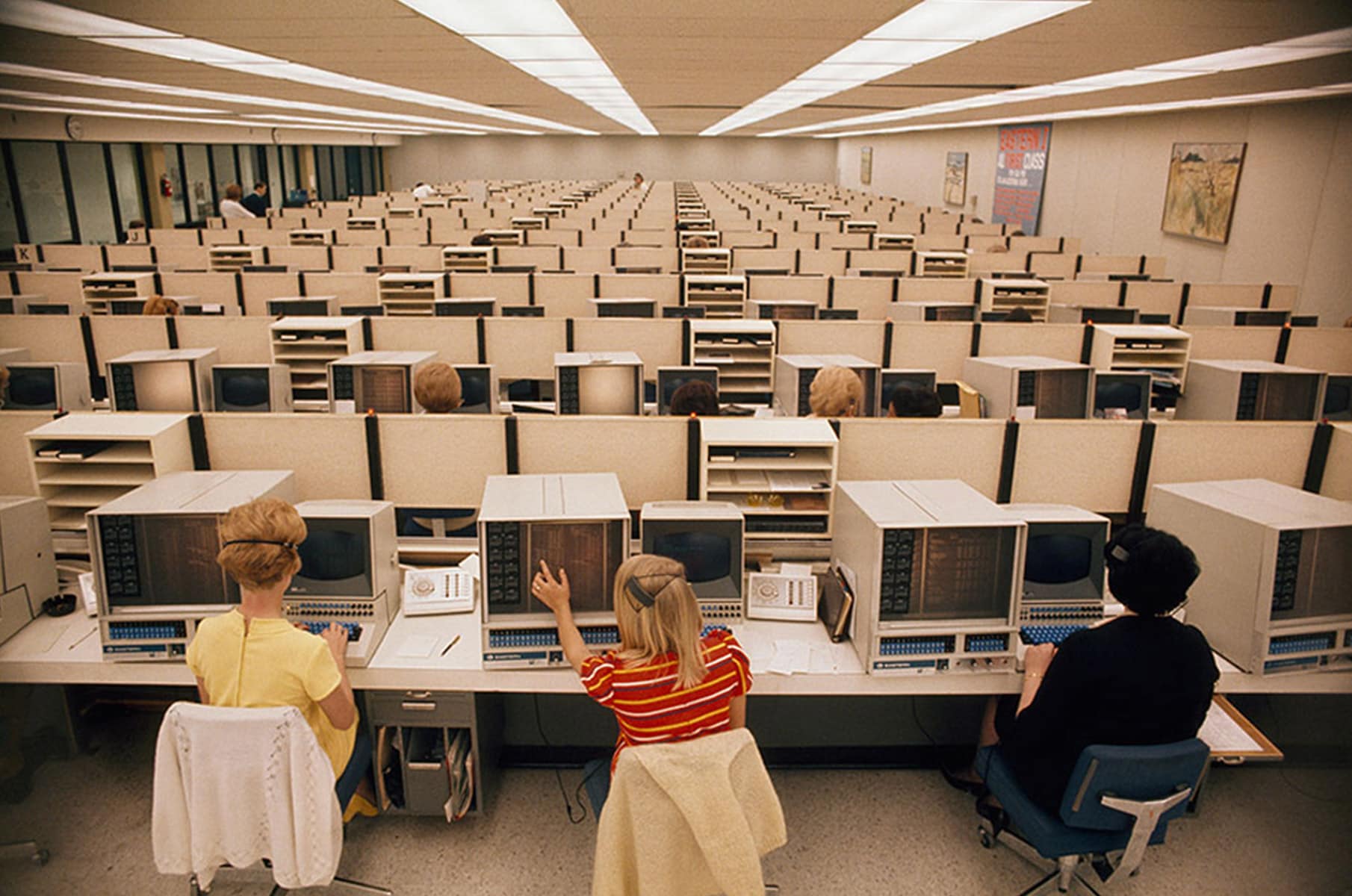

And it isn’t just org charts. Most current business operations were developed during the Industrial Revolution — when modern workplaces were forming around the machines that made the work possible. This included railroads, but also emerging plants and factories that churned out the many new mechanical inventions of the day.

Much like with Daniel McCallum of the Erie Railroad, this necessitated a new style of management — one that asked employees to perform simple, repeatable tasks. The most important qualities of any worker were that he be reliable yet replaceable.

Increasingly, this type of labor has been shifted offshore or automated by software to execute repetitive tasks. Which means that today, that mentality feels outdated even if you do work in manufacturing. The work that’s left requires problem solving, creative thinking, and the ability to innovate. And any good business leader knows that you achieve that with people — the lifeblood of the organization.

There was a time when the nature of work encouraged mechanistic thinking — imagining your employees like cogs in a machine. But much like buggies and typewriters, culture is ready for a more modern approach. Here are some ways you can bring your organization into the 21st century.

It’s no secret that a good culture is built on trust… but this has unfortunately manifested more as a dreaded “accountability tool” than a culture of shared respect. Many business owners have been burned once or twice by an employee taking advantage — which can be a difficult financial burden. Not wanting to be fooled twice, they build a low-trust culture to protect themselves.

The unintended consequence? Your employee doesn’t trust you either.

By holding people accountable to each other (rather than to leadership or arbitrary metrics), you’ll unite them toward a shared goal rather than using accountability as a cudgel to beat them into compliance.

It’s been in vogue in recent years to call employees “your most valuable asset.” The intention here might be good, but (as we’ve discussed on the Kinesis blog before) words are everything. And what does a word like “asset” convey? To borrow from Wikipedia:

“An asset is any resource owned by a business or an economic entity. It is anything (tangible or intangible) that can be owned or controlled to produce value.”

Now, imagine telling an employee on their first day that you see them as something to be owned or controlled to produce value.

The same can be said for many of the words we use when it comes to culture — including Human Resources. Humans are not a resource, they are not an asset, they are not a cog in your business machine. In fact, they quite literally are your business. Without them, you wouldn’t have one. How can you redefine your idea of “Human Resources” to account for this?

For starters, you can completely reposition and professionalize this role, and think of them as an executive rather than a function. HR (or more fondly, the People Department) should not be treated like babysitters, and their role should extend far beyond conflict resolution and processing 401k paperwork. Elevate them to be the champion of your people and the very shepherd of your culture.

Speaking of HR, don’t shove them three layers deep in your organizational structure — which is frankly where great HR leadership skills go to die. So many org charts list HR under “Finance” or “Operations” which does nothing to emphasize the essential nature of their role. The department in charge of people is the most important in your organization — and your org chart should reflect it.

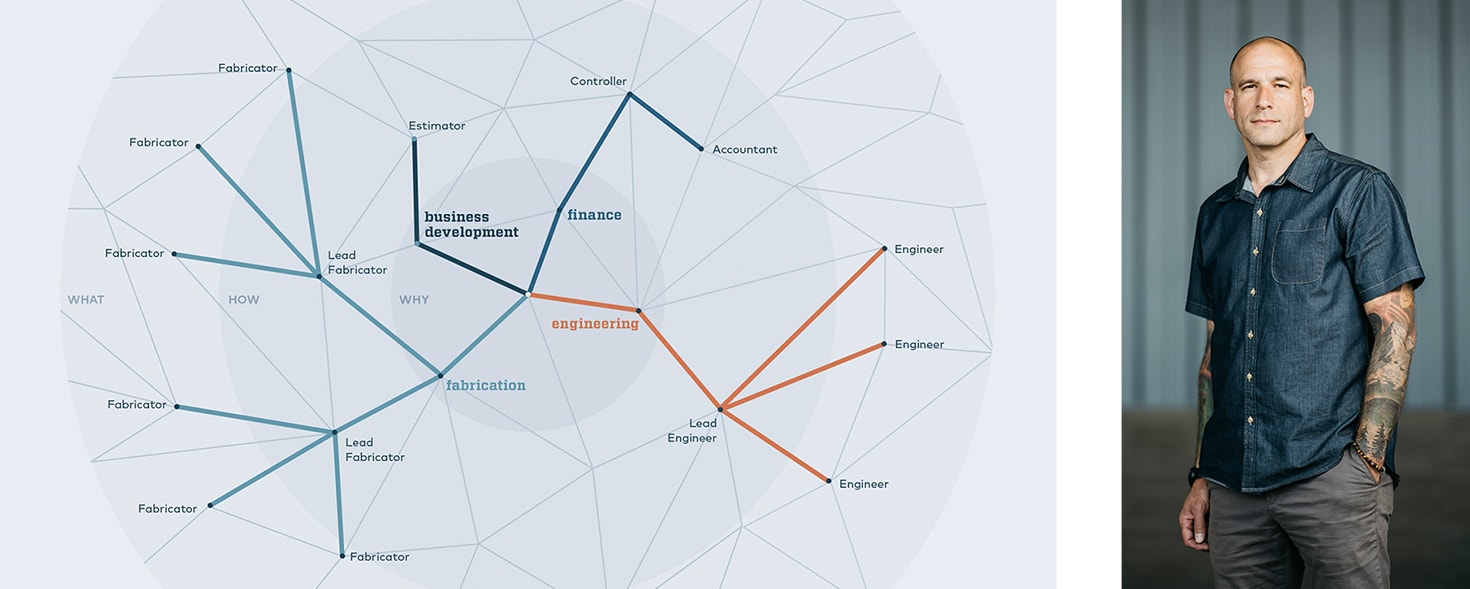

But while you’re at it, you may as well re-think the hierarchy of your org chart altogether. Unless you’re building 500 miles of railroad without the benefit of modern communication devices, chances are the old model doesn’t suit your business.

Maybe your org chart doesn’t need boxes. Or pyramids. Or top-down thinking. What if you did like Deven Paolo of Solid Form, and imagined an org chart that starts with “why?” Or built one around the united purpose of cross-functional teams (rather than silos)? Consider ways you could abandon the traditional management layers to tell a different story.

These are new ideas, and new ideas are often uncomfortable. It would be easy to fall back on the methodologies with which we’re familiar, because the alternative is uncharted territory. It would be easy to treat people like machines or “assets,” keep your current org chart structure, and hold people accountable to KPIs.

It also would’ve been easy to keep burying our food in the ground and traveling on horseback.

When you treat your team like humans, you empower them to be their best selves — and rather than being a cog in the machine, they bring possibilities to the table you never could have imagined. What could be possible for your business?

Interested in learning how Kinesis helps businesses rethink culture (and more)? Check out our True North process.

Get insights like this straight to your inbox.