Why a best-kept secret isn’t as delicious as it sounds

It’s time to take your organization from the best-kept secret to the next big thing. Find out how!

Last week I read a compelling article on the continued success of Portland’s Wieden+Kennedy. The darling of the advertising world, this small-but-mighty firm serves big players like Nike, Proctor and Gamble, and Old Spice. By focusing on results, the agency has managed to continually win despite the Great Recession. For some perspective on just how good this team is, here’s what the Portland Business Journal had to say about W+K’s efforts:

"Its iconic ads for Old Spice body wash led to a 27 percent sales jump for the company’s deodorants and fragrances after the campaign featuring actor Isaiah Mustafa launched last year. Sales rose 55 percent after the second spots began running and 107 percent after YouTube spots aired."

Reading through the article, I was struck by a comment from W+K’s Portland’s managing director, Tom Blessington. Here’s what the Business Journal had to say about the process of winning new business:

While its hot streak continues, the (W+K) creative staff can generally fore go formal pitch processes. The firm has only won one account through pitch meetings, for 1990s Internet service provider Alta Vista.

“We’re not slick by nature, and when you get into those shootouts, you have to be shinier and slicker,” Blessington said. “We don’t have a patent-pending process (for pitches). A lot of agencies do. That’s reassuring to some clients, but it takes the guesswork out of the magic of creativity.”

In case you’re unfamiliar with the world of advertising, what Blessington says borders on apocryphal. From Mad Men to today, the de-facto method of winning new advertising work is “the pitch;” W+K - one of the most successful agencies in modern times - has shown consistent success despite eschewing the selling methods used by the rest of the industry.

If professional service providers like W+K can succeed without pitching, what about the buying side of the equation? Are buyers well-served when they select partners through alternative processes? Old Spice certainly did…what about others?

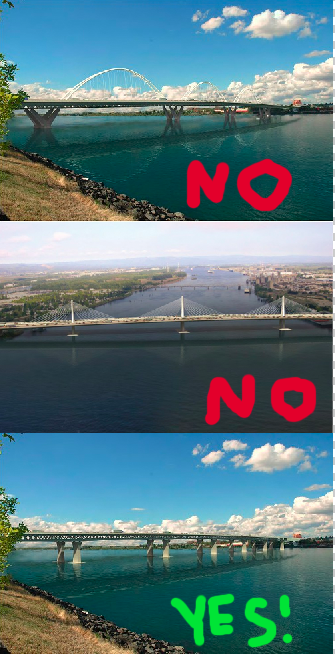

On the border of Portland and Vancouver there’s a problem: namely, an old bridge that can’t support the traffic loads from the state’s main interstate. Built in the 1917, the bridge (known as the Columbia River Crossing or CRC) is neither seismically stable nor wide enough for the 135,000 cars, trucks, and commuters that cross back and forth on a daily basis. The situation gets worse when you consider that the bridge actually closes for river traffic. Current wait times (6 hours per day) are estimated to more than double by 2030.

There’s a great deal of controversy around replacing the bridge, but the point that really hit home for me came in a recent article in the Oregonian. The controversy? The planning process for the new crossing has cost tax payers over $130 million without lifting a single shovel of dirt. Here’s an excerpt that highlights the cost of an inefficient process which yielded a decidedly mediocre bridge design:

"…the Oregon and Washington departments of transportation did not wait for a tidy political consensus. They plunged ahead on the project, building an enormous machine of engineers, architects, biologists, meeting "facilitators," political operatives and public relations specialists dedicated to make the crossing a reality. That machine is burning through about $1.8 million a month, $60,000 a day."

I’m certainly no expert on building bridges, and it’s hard to know what amount the process should have cost. Still, the Oregonian article raises some very disturbing points: even the CRC admits the flawed process resulted in over $100 million in added expense (the photo below is the Portland Mercury's commentary on how the process passed up two remarkable designs in favor of mediocrity).

Most telling about this failed process was how it began: only one firm, David Evans and Associates, submitted (and won) the request for the primary contract. While it’s likely that David Evans is a competent engineering firm, the lack of additional project respondents made me wonder: did the CRC really do its due diligence in picking their key strategic partner? Was it the case that the CRC vetted a field of candidates (satisfied that their top pick was the only applicant) or was their “winner” simply the only firm that showed up?

Inspired by these two sides of the same coin, I’ve written a series of articles in the process of choosing a strategic partner. Specifically, I examine the use of the Request For Proposal (RFP) and ask if it's really the right tool for finding a professional service provider. And, as an added bonus for firms that respond to RFPs, I’ve included a section that outlines how your firm can move away from this high cost method of selling. So stay tuned! Part 1, Digging Holes, comes out tomorrow!

Get insights like this straight to your inbox.