The Sell-Do Trap and How to Escape It

The “Sell-Do” trap describes businesses where the owners are responsible for both selling and delivering the work (they “sell” the work, then “do” the work).

*Note: This is Part I of a two-part series. In Part II, we explore how B2B companies can leverage storytelling in their visual brand and marketing efforts!

Sit down, and let me tell you a story.

President Theodore Roosevelt was an avid bear hunter – and in 1902, took a hunting trip with Mississippi Governor Andrew H. Longino. After three days of hunting, other members of the party had spotted bears… but Roosevelt was still empty-handed.

In an effort to cheer him up, the hunt guides tracked an old black bear and tied it to a willow tree – inviting the president to kill it so the trip wouldn’t be for naught. But Roosevelt took one look at the old bear and refused to shoot it, saying that doing so would be unsportsmanlike.

The story spread, and not long after a Brooklyn candy shop owner put two stuffed toy bears for sale in his shop window – calling them “Teddy’s bears.” Their rapid popularity led to mass-production, and more than a century later “Teddy bears” are still prevalent today.

There – now you’re unlikely to ever forget the origin of the Teddy Bear. Why? Because stories (unlike facts, figures, and bullet points) are our most fundamental communication method.

Since cavemen painted on walls, storytelling has been one of the most unifying elements of mankind – central to human existence and taking place in every known culture in the world. It’s how we learn, instill morals and values, and connect with one another… which makes it a powerful psychological tool when it comes to your marketing.

Storytelling is one of the most unifying elements of mankind... which makes it a powerful marketing tool.

So why this love affair with stories? Believe it or not, your brain is actually programmed to process information through storytelling - that is, it's programmed to recognize patterns of information and assign them meaning. It’s how you learn to associate facial features with a specific person, or music notes with a particular song. Stories, too, are recognizable patterns – and we use them to find meaning in the world around us. We see ourselves in them, and the stories we hear become personal to us.

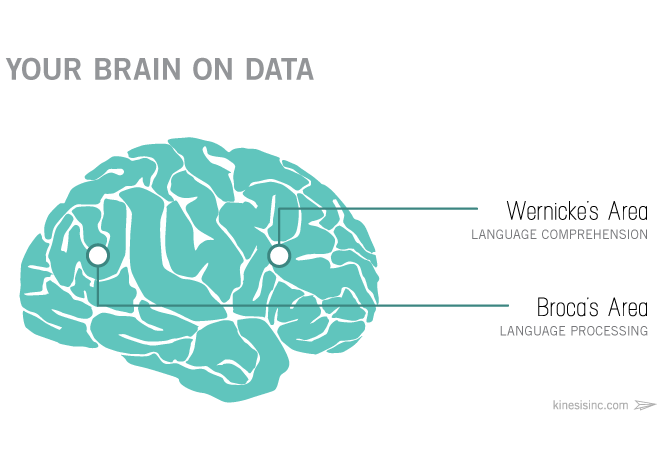

In fact – the personal connection we feel when hearing a story isn’t just theoretical; it’s backed by some interesting neuroscience. Just take a look at what happens when your brain is hearing facts versus when it’s experiencing a story:

If I were to prattle on with sensible information (like the features and benefits of something I’m trying to sell you, for instance), two areas of the brain are activated: the one that intakes the information, and the one that processes it.

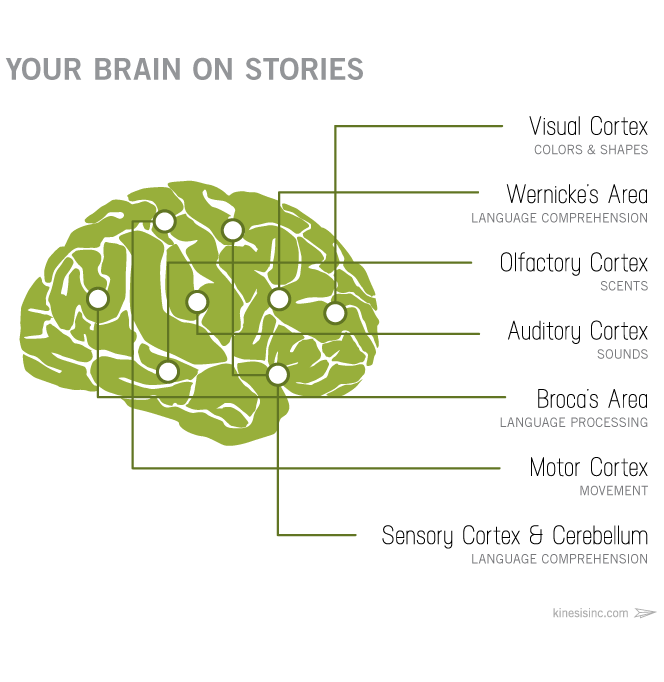

…And that’s it. Your brain acts like a mental file cabinet, accepting the facts and then tidying them away. But if I were to tell you a story instead of just presenting data, many more areas of your brain become engaged:

Interestingly, these are the same parts of the brain that become activated when we’re living out our day-to-day lives. So if, while telling you a story, I say something like “her voice was like velvet” or “he had leathery hands,” your same cerebral areas light up as if you are physically touching velvet or leather.

Yes, you read that right: Your brain actually can’t tell the difference between hearing a story and experiencing it. Because of that personal connection, we become deeply emotionally attached.

Your brain can't tell the difference between hearing a story and experiencing it.

And that emotion does more than just tug at our heartstrings – it can actually have substantial influence on human behavior. Neuroeconomist Paul Zak found this out in a series of experiments which connected storytelling to generosity.

In the experiment, Zak asked two groups of people to donate money to a stranger. But before asking, he showed one group a short animated video about a terminally ill boy named Ben. He found that the group exposed to the video story had higher levels of oxytocin in their brain – a neurochemical that caused them to be more inclined to donate money (regardless of the fact that the donation and video were unrelated).

In fact, Zak was actually able to predict who was most likely to take the desired action (in this case, donating money) by which people felt a current emotional charge – and those who heard the story were 80% more generous than those who did not.

Okay, so maybe stories eliciting an emotional response or inciting action isn’t altogether surprising. After all, we’re emotional creatures – as evidenced by the fact that we all still get teary at that Budweiser puppy love commercial:

But what if I told you that in addition to emotion and action, stories actually have the power to change our perceived value of something?

That was the conclusion drawn by the Significant Objects Project – a literary and anthropological experiment that set out to answer the question: Can a great story affect an object’s subjective value?

The team purchased seemingly worthless trinkets at thrift stores and asked some creative writers to invent stories about them. They then posted the objects (with their stories) on eBay to see whether the invented story enhanced each object’s value. And it did: The trinkets, originally purchased for a total of $128.74, sold for a whopping total of $3,612.51 – a 2,700% markup.

In other words, after watching that puppy commercial we’re not only more likely to buy a Budweiser… we’re likely to pay more for it.

Pop Quiz: What’s the history of the Teddy bear? You remember (or at least I hope you do), because of an effect discovered by neuropsychologist Alexander Luria – who is best known for his work related to human memory. In one experiment he read off a series of arbitrary words to patients, and asked them to recite them back. None were able to do so. However, when he encouraged patients to envision the words in a story – say, by imagining that they were walking down a street and passing each one – their retention rates increased significantly. (Download PDF study)

This became known as “The Story Method” of memorization – used in everything from Alzheimer patients to college students studying for tests.

So what does this all have to do with marketing? In short, everything. Take the Marlboro cowboy, which went national in 1955 and is one of the most successful brand story examples of all time: Basing the brand’s personality on the rugged, uncompromising, and independent cowboy resulted in a 3,241% increase in Marlboro sales.

It wasn’t that people consciously aspired to be cowboys. It’s that they wanted to show the world they were rugged, uncompromising, and independent… and were prepared to modify their purchasing behavior to favor a brand that helped them communicate something meaningful about themselves.

People are prepared to modify their purchasing behavior to communicate something about themselves.

The power of identifying a brand with a familiar story is that it already exists deep within our subconscious — it doesn’t need to be created. Which means that in low-engagement contexts like a website (where you only have seconds to make an impression), brand stories requires less cognitive processing. It’s like saying, “You know that one thing you love and trust already? This is like that.”

So the next time you want to engage a customer, sell a beer, or educate someone on stuffed animal trivia… harness the power of storytelling, and see what happens.

Ready to learn more? Check out Part II, in which we explore how B2B companies can leverage storytelling for growth!

Kinesis helps clients tell their story in a clear, authentic way through our comprehensive branding and marketing process. To see some of our work, check out our Portfolio.

Get insights like this straight to your inbox.